The Building Blocks of Omnichannel Fulfillment

How leading brands snap together their omnichannel mix to meet market needs and expectations while serving business goals.

E-commerce growth, accelerated by the pandemic combined with organic changes in customer needs and expectations, has forced both business-to-consumer and business-to-business (B2B) brands to adjust their omnichannel mix.

Consumers are driving much of the change, with 82% of those in the United States noting that “convenience” is important when shopping for non-essential items, according to research by e-commerce fulfillment provider PFS. While convenience can take many forms, it often involves options such as buy online pickup in store or faster delivery than in the past.

Consumer expectations for selection and delivery speed carry over to the B2B side, as well. Business customers accustomed to getting same-day or next-day delivery in their personal lives, for example, have come to expect that from their business suppliers as well.

How are retailers adjusting their omnichannel mix to meet business goals and customer expectations? Here’s how three brands built significant, lasting, and successful changes.

Extreme Customer Service: Same-Day Delivery

Gordon Food Service (GFS) has been “passionately committed” to its customers since 1897, so when it noticed an increasingly common problem with some of them, it looked for a solution.

As the largest family-operated broadline food distribution company in North America, GFS delivers to restaurants, healthcare institutions, and schools in the United States and Canada. The Michigan-based company also sells to restaurants and the general public through more than 175 retail outlets in 12 midwest and northeast states.

While restaurant customers receive weekly product deliveries, they often run out of key ingredients they need to replace quickly, usually by sending someone to a supermarket or a GFS store. GFS saw this pain point as an opportunity to provide an even higher level of customer service by offering supplemental same-day and next-day van deliveries from its stores.

After piloting the deliver-from-store service on a small scale using existing, but inadequate, systems for order-taking and manually routing deliveries, the company knew it could deliver—literally—on its same-day promise. Scaling the service presented challenges, but GFS now leverages its last-mile strategy as a competitive advantage in 104 of its stores.

The company’s enhanced online order management system (OMS) has visibility into both store and warehouse inventory so it knows if an “I need it now” order is in stock at the closest store, or has to be delivered to the store from the warehouse the next morning.

Picking speed is important with in-stock orders because employees are competing with shoppers for products, so when there’s an order to fill, the OMS announces the news through the store’s public address system.

“If there’s one loaf of bread left on the shelf, we need it for the online order or else we are confirming quantities we don’t have,” says Al Contreras, GFS customer innovation manager.

Last Ordered, First Loaded

The OMS also eliminates the same-day delivery option every day at a configurable time, and removes that option sooner if the morning’s orders max out van capacity. In addition to routing deliveries for the refrigerated vans according to customer locations, the FarEye delivery management platform integrated into the system determines van loading flow so the last order is loaded first.

To keep the focus on customer service, a store can instruct FarEye’s routing software to split one van’s load into two so there’s no risk of a late delivery. “It takes more fuel, but I’d rather send two drivers out with half-full vans and get them to the customer on time than overload one and risk running late with any of them,” Contreras notes.

That strategy has paid off. GFS sales increased 8.6% in 2021; the company credits the last-mile omnichannel strategy for 36% of that growth.

“It was the right thing to do for our customers and our business,” says Contreras.

Large Brand Sells Direct to Smallest Retailers

In India, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) normally move through more than one wholesale layer before they reach the shelves of the small mom-and-pop shops that sell about 80% of the category’s products in that country.

Looking to simplify its supply chain, get better market data, and move closer to its end consumers, Hindustan Unilever (HUL), the country’s largest FMCG manufacturer, created a business-to-business ordering platform for the region’s smallest retailers in 2020.

More than 800,000 small retailers now use the Shikhar app, which allows them to bypass middlemen and place orders directly with the manufacturer for next-day delivery. It also provides access to inventory financing through a State Bank of India partnership. And, it generates data that both the manufacturer and retailers can use to refine business operations.

Allowing the mom-and-pop shops that dominate the Indian landscape to order directly, however, requires significant distribution center changes.

“Like all FMCG companies, small businesses usually supply full boxes to the big grocers and distributors,” says Pieter Feenstra, CEO of Addverb EMEA, a global robotics company based out of India. “But the small mom-and-pop shops will not order a full box of shampoo—they will more likely order three bottles. So some of the HUL distribution centers that supplied full boxes all of a sudden had to begin picking eaches.”

Enter Samadhan

As part of that shift, HUL piloted Samadhan, an innovative, direct-to-trade order fulfillment center in Chennai. Built adjacent to an existing facility that supplies large quantities of boxes to larger stores that include big box-type retailers, it is fully integrated with the manufacturer’s digital order capturing platform.

By using Addverb robotics and software, the company can provide fast, reliable service to retail outlets through warehouse automation and optimized last-mile logistics.

Automation pulls full cases from the first warehouse to the second, where employees decant the merchandise into plastic crates from which they later pick individual orders. The system uses a sophisticated conveyor traffic system for goods-to-person picking, storing completed orders, and moving the sealed crated orders in optimized route sequence to delivery trucks. Trucks pick up empty crates when delivering orders, returning them to Samadhan for reuse.

Because the pilot center uses double-deep storage and retrieval and has optimized the picking process, it can operate on a smaller footprint than less automated facilities. Automation makes it possible to reduce the number of employees during a tight labor market.

With the recent addition of direct-to-consumer sales, which also require fast order fulfillment, HUL is exploring implementing the pilot model in other warehouse locations as well.

Beauty Brand Implements Multi-Node Fulfillment

While many consumer brands struggled to maintain their customer base when stores closed during the pandemic and shoppers were forced to buy online, “nonessentials” selling on Amazon were especially hard hit.

“Amazon prioritized essentials like toilet paper and hand sanitizer in its distribution centers, resulting in delays and reductions in other product categories such as luxury or prestige beauty,” says Kamran Iqbal, commerce strategist at e-commerce fulfillment provider PFS.

The solution for one of PFS’s high-end beauty brands was to leverage its presence on other existing online retail channels, including its own branded website.

The challenge was to make sure its e-commerce operation could protect the brand’s reputation for quality by handling the volume increase quickly and efficiently.

Working with PFS, the company implemented a multi-node fulfillment strategy that included adding two distribution centers and turning 10 branded brick-and-mortar stores into micro-fulfillment centers.

The fulfill-from-store plan started with non-mall locations that employees could access while stores were still closed to the public.

“Critical to our ability to support that strategy was that this company already used our order orchestration and order-to-cash platform,” says Patrick Lowe, area vice president of business management for PFS. “Because we had the OMS connected to their IT infrastructure, front-end e-commerce platforms, and back-end ERP, we could open additional solutions quickly and agilely.”

From Technology to Process

With the technology in place to access store inventory and route orders to stores, process came next. “We shipped them the same packaging supplies that we used in our warehouse management program,” Lowe says.

The shift in omnichannel to incorporate store fulfillment—which remains in place post-pandemic—allowed the brand to avoid disappointing customers while also offering a new way to engage with them through curbside pickup and later, in-store pickup, as well.

There’s an ancillary benefit to this pandemic-forced shift: It helps reduce the brand’s carbon footprint, something that’s increasingly important to customers.

Overnight and two-day shipping for premium and other brands often means the order travels first by air, then by ground. “One way to achieve sustainability is to reduce dependency on air shipments and the time it takes to move a package from point A to point B in any kind of vehicle,” says Iqbal. “Leveraging this multi-node, dynamic fulfillment network is how some brands are trying to achieve their sustainability objectives.”

It’s a bonus benefit of the omnichannel mix adjustment for both the beauty brand and its customers.

Reshaping Omnichannel Retail

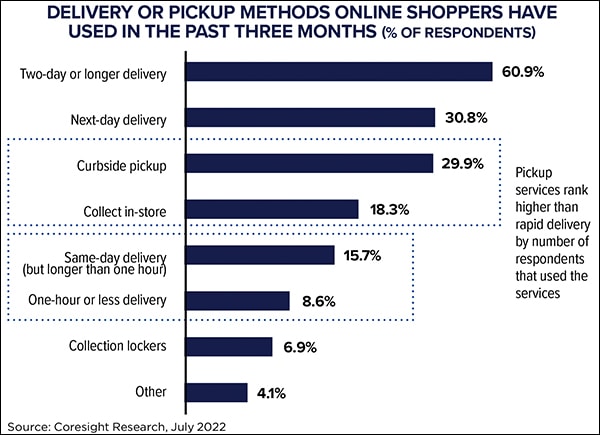

The rise of pickup services has given brick-and-mortar retailers a much stronger value proposition, bringing together the strengths of online and offline shopping to create more choice and flexibility for customers. Merely offering these services to online shoppers, however, is no longer enough. Retailers should look to boost the efficiency and quality of these services through enhanced training, technology and store designs.

Implications for Retailers

To better support pickup service, retailers need to optimize store layouts to offer better access for shoppers. Put pickup counters near the front door for easy and quick access and allocate dedicated fulfillment areas or parking spots for pickup near the store entrance.

Retailers should look to promote their collection offerings over delivery in less dense, suburban and rural areas. As these services transfer the cost and responsibility of the last mile to the customers, it can lead to less margin squeeze than a delivery service, which is more suitable for urban locations.

Retailers can highlight pickup as a more affordable alternative to home delivery, showcasing the savings associated with lower fees and no additional surcharges or tips, to retain online customers in the current inflationary environment.

The jury is still out on pickup lockers as an investment for many U.S. retailers. However, locker service has the potential to be adopted on a greater scale due to the convenience and labor-cost benefits the format has over other last-mile options. As with logistics and fulfillment automation, retailers must weigh those advantages against the investments required.

Implications for Technology Vendors

Because consumers must engage with retail locations to access buy online pickup in store (BOPIS) and curbside pickup, these services provide unique opportunities to generate impulse consumption versus delivery. Technology vendors should offer a functionality that triggers push notifications to inform customers of in-store offers and deals and prompts them to add impulse items to their cart once they enter the geofence. To reduce complexity, retailers can feature a limited impulse assortment, allowing store associates to easily locate these additional items and pack them into customer bags as needed.

Technology providers can add features that would help retailers identify customers who have experienced longer wait times and kick off proactive marketing campaigns to win them back.

– Coresight Think Tank, Coresight Research, July 2022