Retailers Come Closer to Home

E-commerce companies are reworking the twists and turns in their distribution networks to get closer to their customers and speed delivery times by shortening the last mile.

Lockdowns and social distancing may have concluded in most of the United States, but consumer appetites for e-commerce purchases and fast delivery has not.

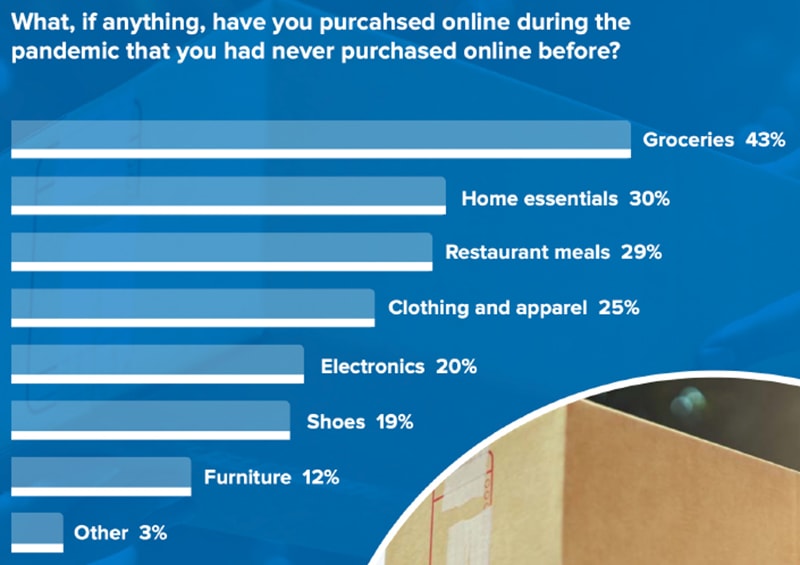

The extent to which consumers rely on last-mile delivery is highlighted in Anyline’s May 2022 survey, Last-Mile Delivery: Customer Perception Report 2022. It was no surprise that many consumers bought items online over the past three years that they previously would have purchased in person: 43% of respondents procured groceries online, 30% bought home essentials, and 29% ordered restaurant meals over the internet.

But as e-commerce becomes more commonplace, so does poor final-mile delivery experiences. Nearly half of respondents told Anyline that delivery timeframes slowed down since the onset of the pandemic, and 68% of consumers have experienced delivery delays.

These dreary numbers could be viewed as an opportunity—96% of consumers indicated a desire to track shipments while en route, and 88% want the ability to redirect a shipment. By deploying a last-mile strategy that puts consumers in control, companies can foster customer loyalty and bring in new patrons as well.

One major contributor to changing expectations is Amazon. Consumers shopping with the e-commerce giant have the ability to purchase an item and have it arrive within days—or hours—of placing an order.

This has precipitated an assumption among consumers that all retailers will offer short delivery times and a high degree of visibility.

“Retailers have stocked forward distribution centers with commonly ordered inventory outside of most major urban areas,” explains Adam Kline, senior director of product management at Manhattan Associates, a supply chain software provider based in Atlanta.

“The idea was to get closer to the customer, and ultimately drive next-day shipping,” he adds. “Consumers can order canned wet dog food from Amazon at 10 p.m., and it’s on their doorstep at 7 a.m. the next day. It’s very disruptive to other retailers.”

The Amazon Effect

E-commerce growth since 2020 accelerated the “Amazon effect.” The pandemic contributed nearly $219 billion to digital sales in 2020 and 2021, according to e-commerce researcher Digital Commerce 360. Keeping up with the volume of online transactions driven by the pandemic can be a challenge for companies without a robust final-mile network built out.

“Shippers often have to rely on a patchwork of providers,” says Andy Dyer, president of transportation management at logistics solutions provider AFS Logistics.“There’s inconsistency in operating quality and process, which can be a challenge for a national brand.”

Building a Network That Doesn’t Cost an Arm and a Leg

To keep up with heightened delivery expectations, some companies are building their own networks of distribution centers or cross-docks. This allows shippers to reduce the number of deadhead miles driven.

Cost is an important factor for shippers considering adding warehouse capacity to their network. Organizations need to weigh the expense of renting or operating an additional facility against driving longer routes. “There’s a balance between the cost of a truck driver and the price of fuel versus the cost of an actual real estate location and the warehouse workers,” says Tyler Higgins, retail practice lead and managing director at management and technology consulting firm AArete. “It ends up being almost a math equation—does it make sense to pay higher rent or even own a warehouse, as opposed to having a long-haul last mile?”

One option to mitigate the expense of building out a network is to focus on sub-regions, Kline suggests. Instead of having one large hub in a central location, shippers could invest in regional distribution centers close to an important customer base.

Shippers in verticals such as grocery are turning to dark stores. These re-purposed brick-and-mortar outlets are located close to densely populated areas to guarantee short delivery times. They don’t accommodate foot traffic; instead, employees move through the store picking items to fulfill e-commerce orders.

“Many retailers are repositioning their store locations as fulfillment hubs,” says Jorge Lopera, vice president for LATAM and industry at FarEye, a delivery management platform. “Some entire malls have been re-purposed for distribution.”

Automation For Last-Mile Fulfillment

Not only do executives have to maintain an adequate network of fulfillment centers, but they must also retain enough labor to accommodate the orders coming in. It’s not an easy task. In an August 2022 Berkshire Grey survey, 57% of responding executives said not having an adequate workforce hampered their company’s ability to meet e-commerce demand.

Automation can optimize the labor that is available. Vecna Robotics, for example, provides autonomous forklifts that automate low-level moves within a warehouse. 3D LiDAR sensors enable the forklifts to navigate around people and objects, and unlike human employees, they don’t need to take breaks.

“Automation allows you to spread out the work instead of doing one furious push over the course of 10 hours,” says Matt Cherewka, director of product marketing and strategy at Vecna.

Another technology that’s optimizing warehouse throughput is autonomous mobile robots, or AMRs. AMRs automate fulfillment picking to reduce a picker’s physical labor while also driving faster turnaround times, explains Mark Wheeler, director of supply chain solutions at Zebra Technologies.

Warehouses that implement AMR technology can see productivity double or triple, according to fulfillment provider 6 River Systems.

Online shopping habits have changed significantly since the pandemic, finds Anyline’s Last-Mile Delivery report. The most popular products consumers purchased for the first time were groceries (43%), home essentials (30%), and restaurant meals (29%), reflecting the realities of store closures and greater demand for products like cleaning materials during the pandemic.

Retail (Outlet) Therapy

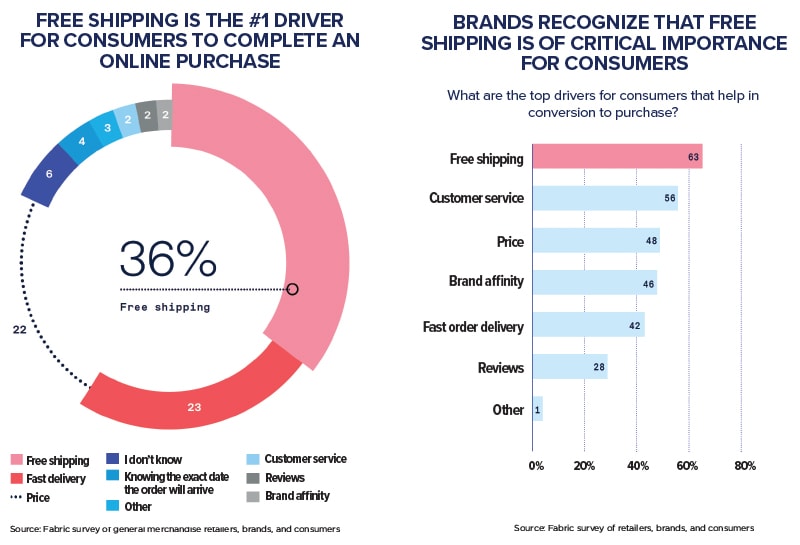

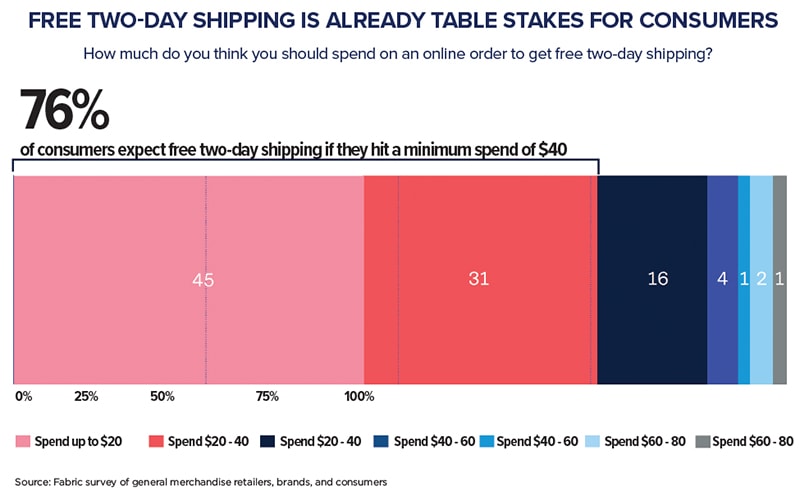

Consumers in 2023 expect fast shipping. In Fast and Free: The One-Way Ratchet of Consumer Expectations, retail technology company Fabric reports that 76% of shoppers expect free two-day delivery with a minimum purchase of $40. And a survey from fulfillment solutions provider Flexe reveals that 85% of consumers will abandon a shopping cart if shipping speed is too slow.

To meet these expectations, some retailers are eschewing new distribution infrastructure, instead opting to fulfill e-commerce orders directly out of physical stores.

In this strategy, known as ship from store, retailers pull items from the available inventory at an outlet. The purchase is then packaged and shipped directly from the brick-and-mortar location, with no additional distribution centers required.

Utilizing an existing store network can shorten the final mile, thereby improving delivery speeds. But its advantages go beyond fast shipping. One example is cost optimization.

“Maybe it’s February in Atlanta. Nobody’s buying winter coats, but a store nearby has a few of them left over,” Kline explains. “That becomes distressed inventory because the retailer has to mark it down 40% off to move those coats.

“If someone in New York is looking at three more months of winter, they might order the same coat, at full price online. The retailer just made back 40%.”

Even without the added expense and planning of traditional distribution networks, ship from store comes with details to iron out, cautions Kline. Sales associates must be trained—and find the time—to pick out and package items for shipment on top of their existing job duties. And stores might have to be retrofitted to accommodate additional activity, especially if they lack an adequate back room.

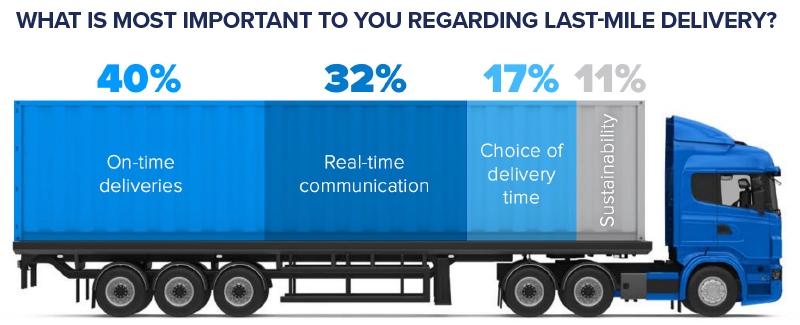

When asked what was most important to them regarding last-mile delivery, respondents to Anyline’s Last-Mile Delivery survey said ensuring their packages are delivered quickly and on time is the top priority. The second most important factor was having real-time communication about the pending delivery, such as notifications of the package leaving the depot, where it is in transit, and when the expected delivery time will be. Having a choice of delivery time ranked third, gaining 17%, while concerns over sustainability ranked last, with just over 1 in 10 (11%) considering it their most important factor in their delivery decisions.

Delivery Window Shopping

As e-commerce grows in popularity, the delivery experience has become foundational to shoppers’ perception of a brand. In The Last Mile Mandate, a June 2022 survey conducted by FarEye, 85% of consumers said they would not shop with a retailer again after a bad delivery experience, while 88% of shoppers reported abandoning an online cart because of poor delivery terms.

One way to avoid that outcome is to tailor the delivery experience to a customer’s preferences.

There are several ways to accommodate customized delivery. One is self scheduling. Ryder, a third-party logistics provider based in Miami, built the RyderView platform that allows consumers to schedule two-hour delivery windows for white-glove orders. Shoppers receive shipping updates via a means of their choosing, and they can reschedule deliveries through the RyderView app.

“RyderView is meant to create the type of experience that the consumer is looking for,” says Jeff Abeson, vice president of last mile at Ryder. “One person taking a delivery might prefer a text and they can press that link and schedule right online. Someone else may prefer to get an email or a phone call.”

Coordinating customers’ preferred delivery windows adds a layer of complexity to final-mile operations. And poorly coordinated routes can compromise service levels, risking the odds of an unsatisfactory delivery experience.

“Retailers struggle with figuring out how to lock in capacity to deliver on service level agreements,” says Walter Heil, senior vice president of developed markets at Locus, a Wilmington, Delaware-based last-mile logistics platform.

“Especially during peak season, first-time buyers make up a higher percentage of orders,” he says. “If it’s a bad experience, that customer might not come back to the website.”

Platforms like Locus calculate optimal final-mile routes, in turn helping shippers procure their desired service levels.

Retailers have a shopping cart’s worth of last-mile delivery options.