Green Supply Chains Come Full Circle

A growing number of organizations are incorporating circular supply chain approaches within their operations. Here’s a look at how they are closing the loop.

For much of the past century, the concept of “planned obsolescence”—designing a product so it becomes outdated or useless within a specific time—has influenced product design.

The concept also impacted supply chains, many of which were created to be linear: Resources are extracted and used to create materials that go into products, which are distributed and, for the most part, eventually disposed of.

This thinking has been steadily shifting. “We’re aiming for planned longevity. It’s the opposite of planned obsolescence,” says John Gagel, chief sustainability officer with Lexmark. Instead of considering disposal the only option for products at the end of their lives, the products become a source of materials.

To promote sustainability, Lexmark offers a cartridge collection program that provides a free and easy way for customers to return its cartridges for reuse and recycling.

Lexmark has been applying circular principles for close to 30 years. To do this, the company has based its product development on three pillars: sustainable design, the efficient use of materials, and responsible reuse or recycling. “You have to intentionally design for reuse and durability,” Gagel says.

For instance, Lexmark specifies the plastic to be used in its laser cartridges and established a return process for them. When they’re returned, as about 40% are, Lexmark can efficiently determine if it will be able to remanufacture the entire cartridge and still meet engineering specifications. Some materials, like resin, can be reused almost infinitely.

In some cases, the cartridges fail to meet design requirements. When that occurs, components within the cartridge typically become a source of raw materials, including plastics, metals, and components.

When Lexmark first began to apply circular concepts, Gagel worked with the engineering team to experiment with different ratios of new and reused resin. They started with a ratio of 95% new and 5% reused. When that proved viable, they moved to 90% new and 10% recycled, and so on. “You have to be willing to try something new,” he says.

Lexmark currently averages about 39% post-consumer recycled plastic in its printers, with a goal of hitting 50% by 2025. Not only has this saved the company money, but remanufacturing also boosts the company’s supply chain resilience.

Like Lexmark, a growing number of organizations are incorporating circular supply chain approaches within their operations. On average, supply chain organizations have been applying circular economy principles for three years to approximately 16% of their product portfolio, finds a recent Gartner survey (see sidebar).

Nearly three-quarters of supply chain leaders expect to boost profits between 2022 and 2025 by applying circular economy principles.

As the survey indicates, a circular supply chain approach can help companies enhance both their environmental impact and their bottom line.

“The linear economy that extracts virgin material creates an enormous amount of waste,” says Hernan Saenz, head of global performance improvement practice with Bain.

In contrast, a circular supply chain can reduce waste and help manufacturers diversify their sources of supply, as used products become a source of materials.

Shifting to a circular operation also may help a company gain market share or offer additional services. For example, along with selling products, a company may offer repair services.

Xerox and Close the Loop’s Recycling and Returns Program aims to achieve zero waste to landfill by collecting and recycling used imaging supplies.

Durability, Style, and Modularity

Subscribers to Fernish gain access to furniture and décor—from bar stools to nightstands to sofas—for the amount of time they need it. The company is in its fourth year of operation.

While it’s still early, indications are that when the company is able to purchase durable, stylish items that can remain in circulation for between about four to seven years, it’s similar to selling the items several times over, says Kristin Toth, president and chief operating officer of Fernish.

As a result, an essential element for sustained performance is identifying products that can hold up through several customers.

“We think about durability, style, and modularity,” Toth says. If a cushion is damaged, can Fernish get another one, while still using the rest of the couch? How “refurbish-able” is the material?

“It’s a great business model, but it’s not for the faint of heart,” she adds.

Also critical is thinking “from a nerdy, operational” perspective, Toth says. The Fernish team developed its own inventory management system after not finding one on the market that would provide even one-third of the capabilities the company needs.

The system tracks all products at the part level. In addition, Fernish knows, for instance, not only that it has one dozen sofas, but that three were in circulation for 36 months, two for 24 months, and seven are still new in the box. Management can use this information to estimate the expected life of each product.

Getting Circular

Implementing a circular approach can offer substantial benefits, but getting there is rarely easy. If a business isn’t founded on the principle of making products to be reused, it’s generally necessary to rethink everything, says Brian Ehrig, partner in the consumer practice with Kearney.

That’s particularly true in sectors that tend to rely on outside parties or vendors to innovate, as the companies themselves will need to engage in more innovation.

Design and material choices also influence the success of circular initiatives. In fashion, for instance, polyester and cotton account for about 80% of the fibers used. Once either are changed by, say, adding color or graphics, they become harder to recycle, Ehrig says.

Through a “circular scan,” supply chain leaders can review their business model for opportunities by identifying products that can be re-used or repaired at their traditional end of life, Saenz says.

This exercise can also include identifying businesses adjacent to the company’s core operations, such as offering repair or recycling services, or providing some products for rental.

Dynamic Disposition

From the start, it’s critical to consider how materials can be reused and repurposed. Since 1959, when it introduced the Xerox 914, the first commercially successful plain paper copier, Xerox has leveraged electronics remanufacturing.

When a device comes back from a customer, Xerox engages in a “dynamic disposition process,” says Al Gallina, vice president, global manufacturing and Americas supply chain operations. The most extensive process is remanufacturing the device, as it involves disassembling it to its elemental parts and building it back up.

In some cases, Xerox will remanufacture and then test the major components and sub-assemblies, which it will use to support repair needs. The parts or assemblies are remanufactured to a “same as new” quality level, with no expectation of lower performance.

“There’s no conceding quality,” Gallina says.

Another option is to recycle base materials like plastics, metal and glass.

In 2021, more than 6,400 metric tons of equipment and parts-related waste were diverted from landfills and recycled at Xerox’s U.S. Reverse Logistics Center. Also in 2021, more than 1.9 million of the company’s toner cartridges were manufactured using recovered cartridges. More than 99% of products that come back are diverted from landfills.

To eliminate single-use packaging in Walmart’s InHome Grocery Delivery Program, Returnity custom-designed a durable reusable bag and a collection and cleaning system that increased performance through tech integration and an enhanced customer experience.

Packaging: Searching for Dumb, Cheap, and Easy

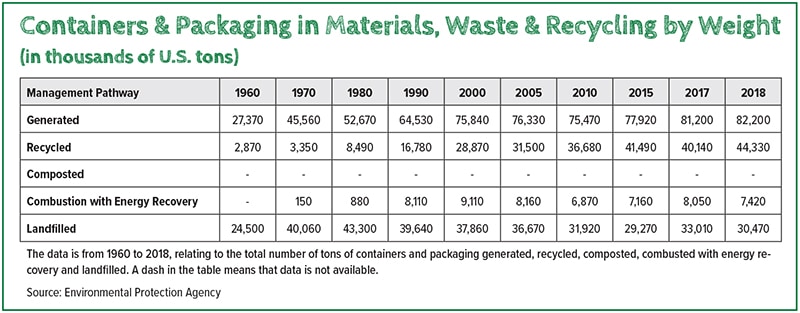

One logical place for many companies to introduce circularity is in packaging. In 2018, more than 30,400 tons of packaging and containers ended up in landfills, the EPA says (see chart above).

Reusable packaging can reduce this number, although challenges exist. One is finding an effective substitute for cardboard, a commonly used packaging material.

Cardboard is “dumb, cheap, and easy,” says Mike Newman, chief executive officer with Returnity, which designs, manufactures and implements reusable packaging and circular logistics systems. To attract users, a replacement needs to be similarly dumb, cheap, and easy, Newman adds.

Even then, getting consumers to return packaging in enough quantity that using recycled materials pays off has been a struggle. Because reusable packaging is designed for durability, its production is more material- and energy-intense, Newman says. If reusable packaging isn’t returned, the additional material and energy used in making it becomes pointless.

Returnable Packaging Plays a Role

Returnable packaging can be a solution for some consumer companies, however. For instance, it’s often a fit for companies that rent outdoor equipment, since their customers will return the products anyway. And, some traditional retailers are starting to use it.

When it comes to internal logistics, like shipments moving between distribution centers and stores, returnable packaging often can play a big role. Employees can be trained and then held accountable for how they handle packaging.

Returnity’s reusable packages are used in about one million shipments and deliveries each month, with a return rate of about 95.5%. Each is individually barcoded, and can integrate with an organization’s warehouse management system.

Between 2020 and 2021, Applied Industrial Technology shifted from pallets and cardboard to reusable containers from RPP Containers for its “milk runs”—moving products from its distribution center to service centers and back.

“It’s safer, cleaner, better for the environment and more cost effective,” says Tracie Longpre, vice president of supply chain. Not only are the containers reusable, but they’re more durable than cardboard boxes, so products are better protected.

The containers are stackable, allowing Applied to improve truck capacity utilization. Truck placement is easy and efficient. Additionally, the containers fold flat for return from their delivery locations, enabling more efficient backhaul. Shipping areas are kept clean without the clutter of cardboard, shrink wrap, and void fill.

When receiving products from vendors, Applied also reuses any package filler and dunnage for its outbound shipments. “Rarely do we need to purchase any,” Longpre says.

Eliminating waste from the start of a manufacturing operation has a tremendous impact on its environmental impact. This is where HILOS focuses.

Its design, development, and infinite restock platform enables brands to launch 3D-printed footwear lines. HILOS’ goal is to “build a creative economy without waste,” says Elias Stahl, co-founder and CEO.

Currently, many footwear and apparel companies overproduce by 20%. The reason? It can take 12 to 18 months to bring an item to market. Brands often over-produce rather than risk missing sales.

What’s more, much of the material used to make apparel and shoes ends up on the cutting room floor, as they are in pieces too small to be used in production. And because most shoes consist of numerous parts cemented together, only about 5% are recycled at the end of their life, says HILOS.

By simplifying construction, utilizing new materials, and engineering for disassembly, the components of HILOS shoes can be repurposed for new products at the end of life.

A Shoe-In

By using additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, along with materials that are 80% recycled and 100% recyclable, and by reducing the number of parts in each shoe to just a handful, HILOS aims to change this. In tests, HILOS’ shoes reduced carbon emissions by 48% and water usage by 99%, when compared to industry competitors’ production methods, the company says.

“We’re writing a new rule book,” Stahl says.

Brands also can use the platform HILOS has developed to create their own designs in the same way they’ve been used to, and fulfillment can occur in 72 hours from “click to ship,” Stahl says. 3D printing offers an “incredible “opportunity to reinvent global supply chains,” he adds.

Circularity and Community

As circular operations become more prevalent, more companies will work with each other, Gagel predicts. If a product is returned to a company that can’t use the plastic within it, that company can forward it to another organization that can.

While intellectual property and other challenges need to be addressed, “multiple circular economies” will be the next iteration, he adds.

Along with reusability and recyclability, the impact of returned items on society will gain more attention. “It’s like Expedia for the circular economy,” says Shawn Stockman, vice president of sustainability solutions with OnePak, whose online logistics platform, ReturnCenter, connects shippers, receivers, and carriers.

Many organizations currently consider three to five years the normal life for a laptop. Once that time frame passes, they often purchase new ones.

However, many computers can perform for another several years. When donated and refurbished, the computers may help individuals who otherwise wouldn’t have access to technology to find a job, or access medical care.

Shifting from linear to a circular supply chain operation often requires rethinking your organization’s approach to business overall, and many functions within it. These guidelines can help.

Enlist partners. You’re changing whole systems, so it’s not just a procurement or supply chain problem, Saenz says. Instead, supply chain leaders need to enlist the participation of marketing, finance, and other departments within their organization, as well as their suppliers, distributors, and other business partners.

Educate. Brands need to help customers understand the steps needed to repair or reuse their products.

Manage the change. One adage states that the effectiveness of a solution is determined by its quality multiplied by its acceptance, says Ken Sherman, president of IntelliTrans, which provides supply chain solutions.

If people don’t buy into a solution, no matter how stellar it is, you won’t gain the benefits, he adds.

Leverage internal expertise. The workers who do the actual refurbishing or remanufacturing often acquire tremendous product knowledge.

If, for instance, the legs on one sofa design keep coming off, these employees likely can suggest practical ways to keep this from happening, Toth says.

Engage your trade association. Longpre worked with the Bearing Specialists Association, a group of manufacturers and distributors, to form a sustainability task force.

“Working with your association is a great way to get ideas,” she says.

Address any skepticism. “Keep a level head and use facts and data” to show how a circular supply chain can work, Gagel says.

From a Single-Use Product to a Circular Business

From a Single-Use Product to a Circular Business

The idea for a sustainable home furnishings company came to engineer Felix Böck after he had just given a seminar on sustainability in Vancouver, British Columbia, and a waiter threw away his chopsticks at a sushi restaurant.

“Suddenly, I understood that I had to show people how a circular economy works instead of just talking about it,” Böck says.

He began his startup, called ChopValue, creating coasters and cutting boards from disposed chopsticks, which are usually made of bamboo. The ChopValue team collects 350,000 chopsticks from restaurants in Vancouver each week—70 million in total across its operations to date.

The chopsticks are treated with high heat and pressure at franchise microfactory locations from Liverpool to Bali to create products like shelves, desks, wall panels, and stairs. On its own, ChopValue will not make a dent in the global trash problem. But if other businesses follow suit, the effects could ripple.

Source: Reasons to be Cheerful

Circular Economy as Profit Center

Seventy-four percent of supply chain leaders expect profits to increase between now and 2025 as a result of applying circular economy principles, according to a recent Gartner survey. On average, supply chain organizations have been applying circular economy principles for three years to approximately 16% of their product portfolio.

“There is still such a great deal of untapped potential in the circular economy,” says Sarah Watt, VP analyst with the Gartner Supply Chain practice. “Supply chain leaders can use the inflationary environment as a catalyst to reshape their relationship with materials. Instead of losing materials out of the economy in the form of waste, the circular economy helps capture value.”

Benefits and Barriers of a Circular Economy

The top three circular economy benefits that have been realized in previous years are:

- Minimizing negative environmental impacts

- Shorter and compact supply chains

- Enhanced customer insights

Common observed barriers to applying circular principles include the application of technology to advance circular economy activities, partnering with stakeholders and measuring the results of circular economy approaches, according to the survey.

The survey shows that respondents are making changes to the supply chain including integrating circular economy products into the planning process (54%), adding new capabilities to existing manufacturing sites (42%), and adding new locations for repair/ remanufacturing and waste management which are company owned (36%).

Looking out over the next three years, the focus will increase on procurement, with buyers being incentivized to purchase circular materials (41%).